Mpox outbreak now seen in vaccinated patients

September 26, 2023

Mpox in vaccinated patients

Mpox, formally known as monkeypox, is a viral disease caused by the monkeypox virus, a member of the orthopoxvirus family, and manifests with symptoms similar to smallpox but typically less severe. The disease is prevalent in Central and West Africa and has been recently reported in countries where it was not previously endemic. The disease exists in two distinct clades: the West African clade and the Congo Basin or Central African clade, the latter being more severe and transmissible.

Human Mpox was first identified in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Since then, the majority of cases have been observed in rural rainforest regions of the Congo Basin and across Central and West Africa, including Benin, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Gabon, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Nigeria, the Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, and South Sudan. However, since May 2022, there has been an alarming rise in cases in non-endemic countries, particularly in Europe and North America, linked to travel history. This simultaneous emergence of Mpox in diverse geographical regions where it is not endemic emphasises the urgency for enhanced awareness and knowledge amongst healthcare providers globally, including general practitioners.

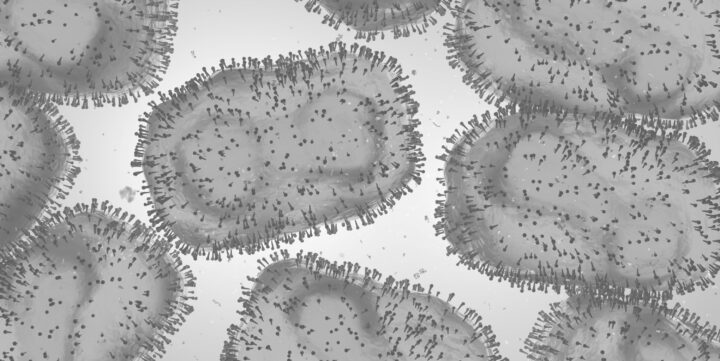

The pathogen

Mpox virus is an enveloped double-stranded DNA virus from the Orthopoxvirus genus of the Poxviridae family. Various animal species, including rope squirrels, tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats, dormice, non-human primates, and others, are susceptible to the monkeypox virus, and it is primarily a zoonosis with tropical rainforests being hotspots for transmission from animals to humans. However, the exact reservoirs of the virus and the mechanics of its natural circulation remain uncertain, necessitating further studies to comprehend its natural history comprehensively.

Clinical presentation

Primary care clinicians need to proficiently identify Mpox and differentiate it from other conditions with similar manifestations, such as chickenpox, measles, bacterial skin infections, and medication-related allergies. The infection typically has an incubation period of 5 to 21 days, followed by the onset of intense symptoms like fever, headache, back pain, muscle ache, and fatigue, along with distinctive skin eruptions. It’s essential to recognize that the initial symptoms post-incubation might not be accompanied by pain and could be persistent. PCR testing, ideally from rash specimens, is the conclusive diagnostic method for Mpox.

Testing

For diagnosis, adhering to the Australian STI guidelines and the RACGP report is paramount. Clinicians should coordinate with local laboratories before specimen collection to confirm the availability of Mpox virus tests like Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (NAAT) or arrange the transport of specimens to the nearest hospital laboratory if needed. Different laboratories might have varied specimen handling requirements, such as double-bagging, so confirming with the local lab before collection is crucial. Specimen material for PCR testing should be collected with a sterile dry swab to avoid leakage and dilution, and if dry NAAT swabs are unavailable, any swab can be used and placed in an airtight container without medium. Multiple lesions should be swabbed with separate swabs, mentioning the lesion site on the specimen containers. If lesion fluid is unavailable, dry crusts or biopsy material can also be tested. Adequate personal protective equipment including gown, gloves, surgical mask, and eye protection should be worn during the collection, and contact with contaminated materials should be avoided.

Furthermore, swabbing suspected Mpox lesions for HSV PCR, syphilis PCR, and LGV PCR is critical, given their role as significant differential diagnoses. Suspected Mpox lesions should also be swabbed for M/C/S due to the common occurrence of secondary bacterial cellulitis. A comprehensive HIV/STI screen should be performed at the time of presentation, considering the frequent incidence of co-infection with HIV/STIs.

Transmission

Mpox is a zoonosis: a disease that is transmitted from animals to humans. Human-to-human transmission occurs through contact with bodily fluids, skin lesions, respiratory droplets, or contaminated objects. Rigorous infection control measures, including personal protective equipment, are crucial in clinical settings. Public awareness regarding avoiding contact with sick or dead animals and consuming only well-cooked meat is paramount in regions experiencing outbreaks.

Recent revelations in the clinical observation of Mpox indicate an unexpected prevalence among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. GPs, especially those in regions with reported cases, should maintain a high index of suspicion for Mpox in patients from these communities presenting with symptoms such as lesions or ulcers in the anogenital area or proctitis, even if they are fully vaccinated. This is essential as Mpox can manifest as progressive lesions in genital, anal, or oral regions and frequently involve the mucosa. A detailed patient history focusing on recent overseas travel or sexual contact with individuals who have travelled internationally in the preceding month should be undertaken, as localised cases have likely been propelled by ongoing outbreaks in regions like Southeast Asia and China.

Any suspected cases should prompt immediate notification to local sexual health or infectious diseases specialists and your local public health unit. Furthermore, healthcare providers should emphasise the importance of vaccination against Mpox, particularly advising men who have sex with men to receive the MVA-BN vaccine, ideally before international travel. It’s pivotal for healthcare professionals to remain vigilant and proactive, considering the ongoing global outbreak and the potential for localised transmission, to ensure the containment of the disease and the safeguarding of community health.

Treatment guidelines

Treatment for Mpox primarily involves supportive care, tailored according to the manifested symptoms, and research is currently underway to explore potential therapeutic solutions. Smallpox vaccines have shown to afford some level of protection against Mpox, and their administration is advocated in areas with populations deemed to be at high risk.

For cases with uncomplicated Mpox infections, recommended management is largely supportive, encompassing pain management, antibiotics for ensuing cellulitis, and stool softeners for patients with anal lesions. Those presenting with severe Mpox infections or identified at heightened risk of severe infection necessitate advanced intervention strategies, such as the administration of Tecovirimat (TPOXX) at a dose of 600 mg twice daily over 14 days for adults. In managing Mpox, the deployment of cidofovir or brincidofovir is not recommended per guidelines, due to limited accessibility and significant toxicity concerns.

The role of General Practitioners is crucial in the early identification, educational initiatives for patients, stringent enforcement of infection control protocols, and endorsement of vaccination, making them indispensable to global endeavours aimed at controlling the spread of this evolving infectious disease.

Weerasinghe, M.N. et al. (2023) Breakthrough MPOX despite two‐dose vaccination, The Medical Journal of Australia. Available at: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/7/breakthrough-mpox-despite-two-dose-vaccination

Wright, Caitlin. (2023) Sexual health doctors urge vigilance on mpox, InSight+. https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2023/33/sexual-health-doctors-urge-vigilance-on-mpox/